It is often said that sport mirrors real life. What is rarely acknowledged is that we all too often treat sport as being different from everything else. In particular we expect it to be played by the rules and don’t (or won’t) understand why some people cheat. The problem with this view is that in real life we are surrounded by cheating of various degrees, some which is overtly frowned upon, some which is somehow ignored. Why should sport be any different?

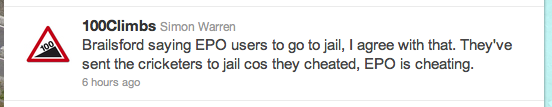

Comments following the cricket match fixing trial made me think about this. One in particular (see below) almost prompted me to respond. But 140 characters didn’t seem quite enough so here is the longer considered version.

Sir Ian Botham yesterday suggested that this was cricket’s “darkest day”. If we are comparing this to the problems faced by other sports Sir Ian and others should probably be prepared for a bumpy ride. As he himself and others have rightly reflected, it is 10 years since former South Africa captain Hansie Cronje was found guilty of match fixing. As William Fortheringham notes in Roule Britannia cycling has faced a drug-related scandal roughly every 10 years since 1967. Cycling is still not out of the woods. FIFA lurches from one allegation of corruption to another, officials are only corrupt if caught after crossing too many swords with the wrong people and yet football remains the World’s sport. And I think we can leave the problems of England’s Rugby Football Union to another time. Here is where sport mirrors life: despite problems, scandals, even deaths, these sports carry on and continue to be played/competed in; and corruption exists, cheats are found out but only after integrating happily in the milieu of that community. Name a part of everyday life and these characteristics exist to a greater or lesser degree. It’s certainly not cricket but then it isn’t in real life either.

That is the first part of the response. The second part is the comparison being drawn with cycling. This is where it is easy to draw quick conclusions but look deeper and the situations are complex and subtly different. David Brailsford and 100 Climbs raise an interesting possibility for deterring cheats through the criminal process. Cricket has had to go through this process at the behest of the Metropolitan Police and Crown Prosecution Service following evidence presented by a newspaper in a sting operation. It is doubtful if this was the route the cricketing authorities themselves would have chosen nor were they seemingly proactive in tackling this issue. Cycling, as with other sports, has already faced the criminal justice system in relation to doping. Joe Papp was recently prosecuted under existing US laws on drug trafficking, The Festina Scandal and Cofidis affair both ended in court appearances and prosecutions in France and France, Germany and Italy, to name just three countries, have adopted laws which class doping as sporting fraud. The “jail the doper” call is a nice soundbite but it is neither innovative nor fair.

To compare match fixing with doping is difficult. Whilst they are both forms of cheating this is where the comparison ends. The aim of a cricket bowler is to bowl the ball effectively enough to gain a wicket and not give away runs. To bowl a no-ball goes completely against this and cheats your own side not the opposition per se. The aim of cycling is to cross the line first and win the race. Doping in order to enhance performance to do this is a logical step and for many has been seen as part and parcel of competing professionally. So immediately we are at odds in comparing the issues. To partake in either is driven by different motives and involves a set of circumstances driven not just by the perpetrator of the crime but by a backroom staff driving the culprit on.

Dopers in cycling rarely do it on their on or for themselves alone, there is a pressure to dope from peers, from sponsors, from public expectation to perform, be that winning or being there to help someone else win. In a way this makes the problem in cycling more logical and, one would hope, more straightforward to tackle. To jail the doper ignores the system which drives them to dope and supplies them with the product, not dissimilar to other drug addicts in real life and we are far from addressing that complex set of problems in our communities. Why expect it to be different in sport.

The popular view is that these Pakistani cricketers were driven by the financial reward cheating would bring. Clearly there’s no denying that but why would they do so if the penalty was not only a sporting ban but a prison sentence. Mohammad Amir perhaps encapsulates the reasons why: born into a non-affluent background one of 7 children, left home at 11 to play cricket, rose to stardom by the age of 19 he had rapidly risen to stardom and now playing amongst some of his heroes. It is not difficult to see how the money earned from cricket helped his family nor is it beyond the realms of fantasy to think that he was under immense peer pressure. As with cycling, it seems that a lack of support from within the team and the influences of key players drove one person to go beyond the line of what is fair and right. It is quite conceivable that financial motives drive the decisions of them all as did the fear of alleged reprisals on their families for not doing as they were instructed, indeed these are more about self preservation that the dopers lament. The 3 cricketers jailed are also victims, whilst they clearly cheated there is a cast of thousands behind them who may never face the consequences of their actions. To address corruption in cricket is therefore not just about the players, it is also about the living conditions from which they and their families come from and the political system in the countries the represent. Again, we are not making great progress in these either.

If only dealing with cheats was so easy, the world would be a better place not just in sport but in our everyday lives. As we witness each and every day that is simply not the case. Ultimately we are all human. Fotheringham illustrates this in his chapter on David Millar in Roule Britannia:

I asked Millar to describe the margin between taking drugs and staying clean. “It’s that,” he says, and holds up finger and thumb in front of me. The gap between them is half an inch. “I was 100% sure I would never dope, 100%, then all of a sudden it was out of control. Cycling had become my life, the only thing that defined me and I resented that. It was ‘fuck it’. It was like flipping a coin. You don’t stop and think. If you think about it, it’s game over.

Good people can do bad things without clear explanation or reason. That is life.

Sport does mirror life warts and all. If we want to address the cheats in the reflection we need to tackle them in real life as well.